Skin functions as the body’s first line of defence against bacteria and viruses, and is also a vital sensory organ, sensitive to the softest touch as well as pain. Healthy skin also maintains the balance of fluids and helps to regular body temperature.

As our largest and most visible organ, covering nearly 2m² and making up almost a sixth of our body weight, the structure and functions of the skin are vital to our overall health and well-being. Understandably, skin conditions can also have a significant impact on our self-esteem.

Skin structure

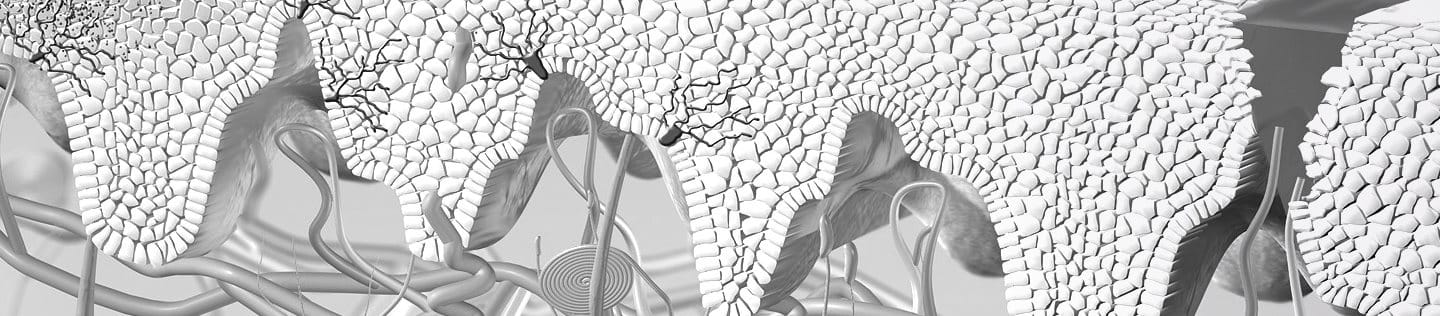

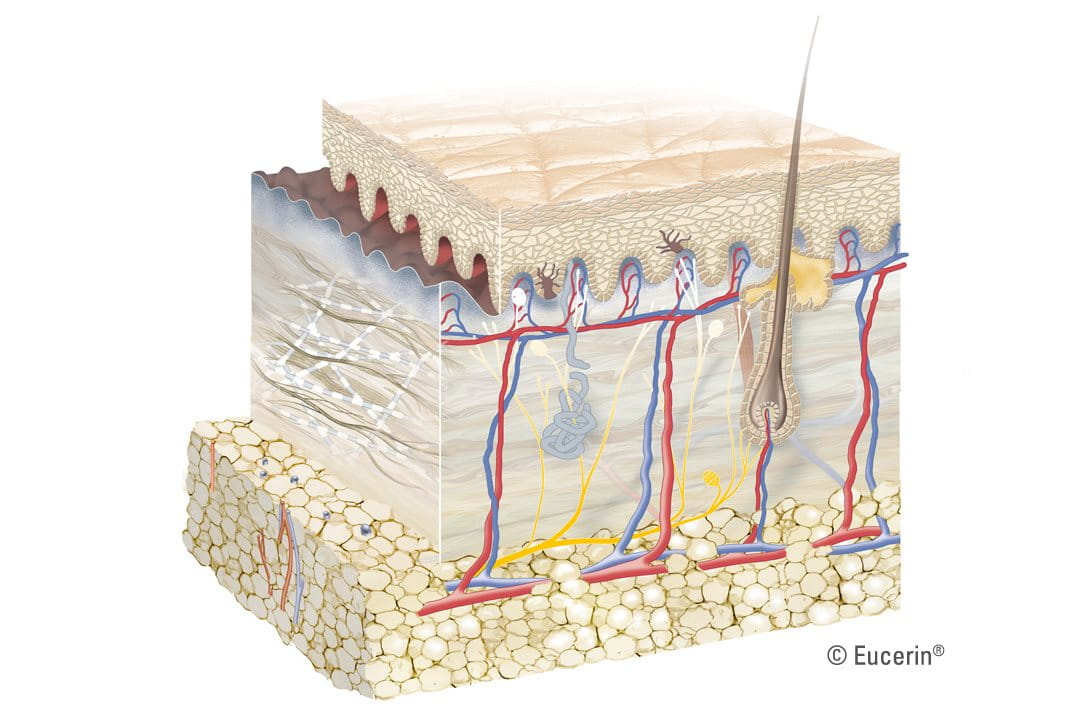

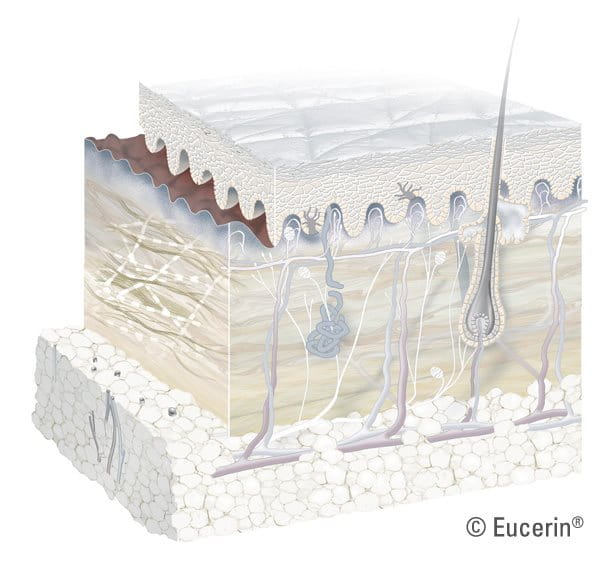

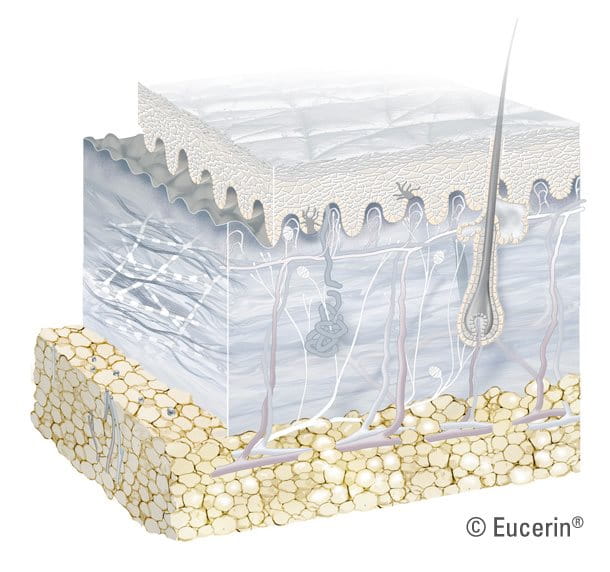

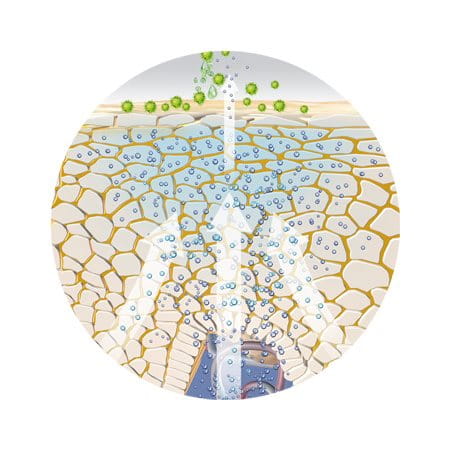

A constantly changing, dynamic organ, there are three main skin layers - the epidermis, the dermis and the subcutis – each of which is made up of several sub-layers. Appendages – such as the sebaceous glands, sweat glands and hair follicles – also exist within these layers, and they play various roles in the overall function of the skin.

Epidermis

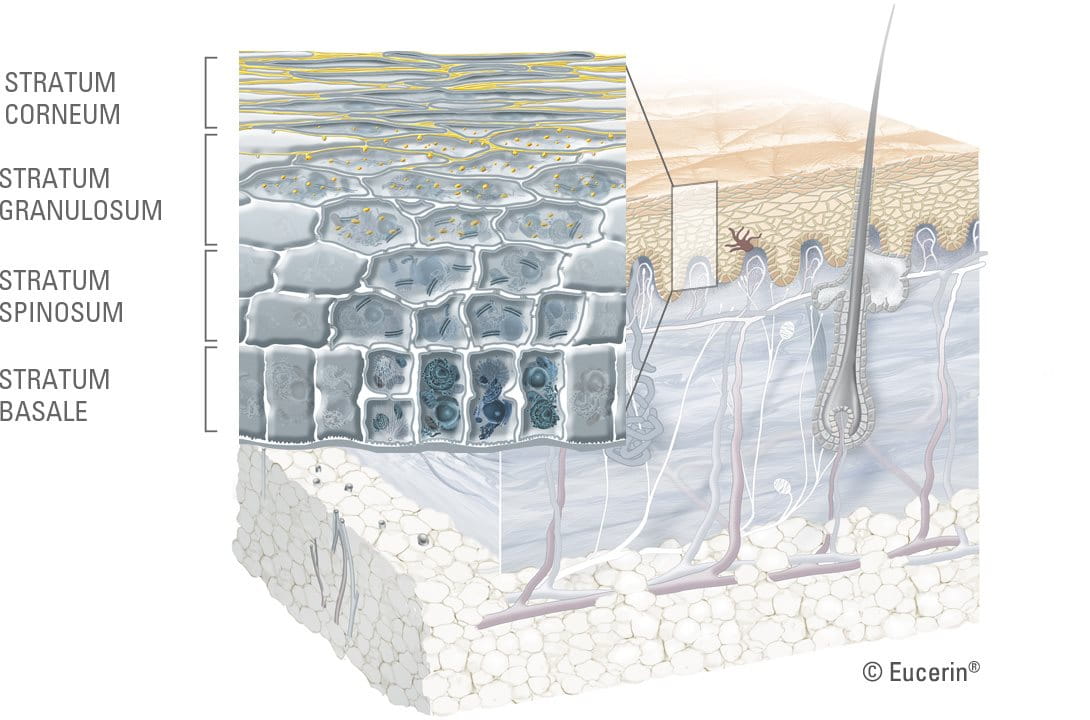

As the outermost skin layer that we see and touch, the epidermis performs skin’s primary function, acting as a barrier to protect us from toxins, bacteria and fluid loss. It consists of 5 sub-layers of keratinocyte cells. The layer of the epidermis consists of 5 sub-layers of keratinocyte cells. These cells are produced in the innermost basal layer and migrate up towards the surface of the skin. As they do, they mature in shape and composition, becoming filled with keratin. This process known as keratinisation (or cornification) makes each of the sub-layers distinct.

- Basal layer (or stratum basale): The innermost skin layer where keratinocyte cells are produced.

- Prickle layer (or stratum spinosum): Keratinocytes produce keratin (protein fibres) and become spindle-shaped.

- Granular layer (stratum granulosum): Keratinisation begins - cells produce hard granules and, as they push upwards, these granules change into keratin and epidermal lipids.

- Clear layer (stratum lucidium): Cells are tightly compressed, flattened and indistinguishable from one another.

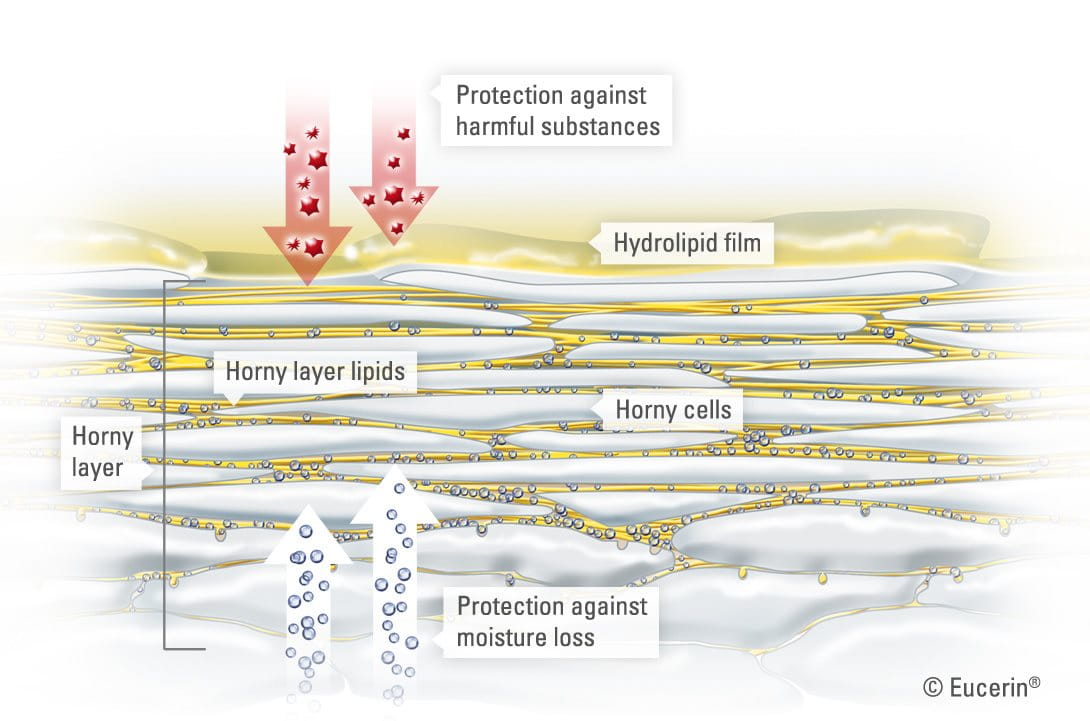

- Horny layer (or stratum corneum): The outermost layer of the epidermis with, on average, about 20 sub-layers of flattened, dead cells depending on where on the body the skin is. These dead cells are shed regularly in a process known as desquamation. The horny layer is also home to the sweat gland pores and the openings of the sebaceous glands.

The cells in the horny layer are bound together by epidermal lipids. These lipids are essential for healthy skin structure: they create its protective barrier and bind in moisture. When lipids are missing, skin can become dry and may feel tight and rough.

The epidermis is covered by an emulsion of water and lipids (fats) known as the hydrolipid film. This film, maintained by secretions from the sweat and sebaceous glands, helps to keep our skin supple and acts as a further barrier against bacteria and fungi.

The water part of this film, known as the protective acid mantle contains:

- Lactic acid and various amino acids from sweat.

- Free fatty acids from sebum.

- Amino acids, pyrrolidine carboxylic acid and other natural moisturising factors (NMF’s) which are mainly by-products of the keratinsation process.

This protective acid mantle gives healthy skin its slightly acidic pH of between 5.4 and 5.9 which is the ideal environment for:

- Skin-friendly microorganisms (known as skin flora) to thrive and for harmful microorganisms to be destroyed.

- The formation of epidermal lipids.

- The enzymes that drive the process of desquamation.

- The horny layer to be able to repair itself when damaged.

Over most parts of the body, the epidermis skin layer is only about 0.1 mm in total, though it is considerably thinner on skin around the eyes (0.05mm) and considerably thicker (between 1 and 5mm) on the soles of the feet. To find out more read understanding skin on different parts of the body and how male and female skin differs.

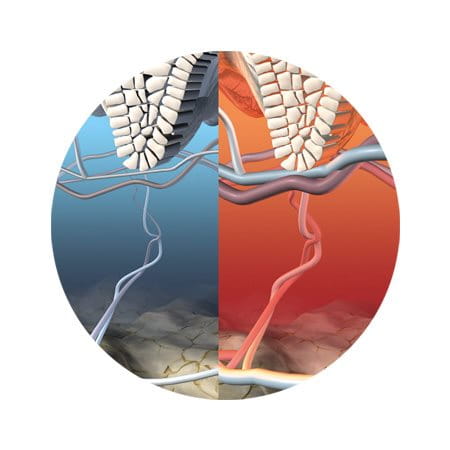

Dermis (or corium)

The dermis is the thick, elastic but firm middle layer of the skin, beneath the epidermis. This skin layer’s main structural components are collagen, elastin, and connective tissues.

These provide strength and flexibility and are vital components of healthy, young-looking skin. The dermis is made up of 2 sub-layers:

- The lower layer (or stratum reticulare): a deep, thick area, which forms a fluid border with the subcutis.

- The upper layer (or stratum papillare): forms a defined, wave-like border with the epidermis.

The dermis’ tissue fibres are embedded in a gel-like substance (containing hyaluronic acid), which has a high capacity for water-binding and helps to maintain the volume of our skin.

The dermis plays a key role in protecting the body from external influences and irritants as well as feeding the outermost layers of skin from within:

- Its thick, firm texture helps to cushion external blows and, when damage occurs, it contains connective tissues such as fibroblasts and mast cells that heal wounds.

- It is rich in blood vessels that nourish the epidermis while removing waste.

- The sebaceous glands (which deliver sebum or oil to the surface of the skin) and the sweat glands (which deliver water and lactic acid to the surface of the skin) are both located in the dermis. These fluids combine together to make up the hydrolipid film.

Lifestyle and external factors such as the sun and changes in temperature have an impact of collagen and elastin levels and on the structure of the surrounding substance. As we age, our natural production of collagen and elastin slows down and the skin’s ability to bind in water decreases. Skin looks less toned and wrinkles appear. Read more in factors that influence the skin, how sun affects skin and skin ageing.

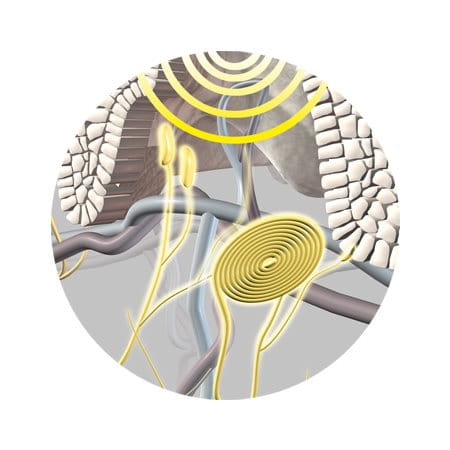

The dermis is also home to:

- Lymph vessels.

- Sensory receptors.

- Hair roots: the bulbous end of the hair shaft where hair is developed.

Subcutis (or hypodermis)

The innermost skin layer stores energy while padding and insulating the body. It is mainly composed of:

- Fat cells (adipocytes): clumped together in cushion-like groups.

- Special collagen fibres (called tissue septa or boundaries): loose and spongy connective tissues that hold the fat cells together.

- Blood vessels.

Subcutaneous fat sits underneath your skin, and its concentrations vary throughout different parts of the body. It differs to visceral fat, which accumulates around the body as a result of diet and other factors.

Moreover, the distribution of fat cells also differs between men and women, as does the structure of other parts of the skin.

Skin changes during a person’s lifetime. To find out more read skin in different ages.

Skin function

Skin is essential to our overall health and wellbeing. Healthy skin is a vital sensory organ, regulates body temperature and fluid balance, and acts as a barrier between your body and the outside world.

Skin as protection

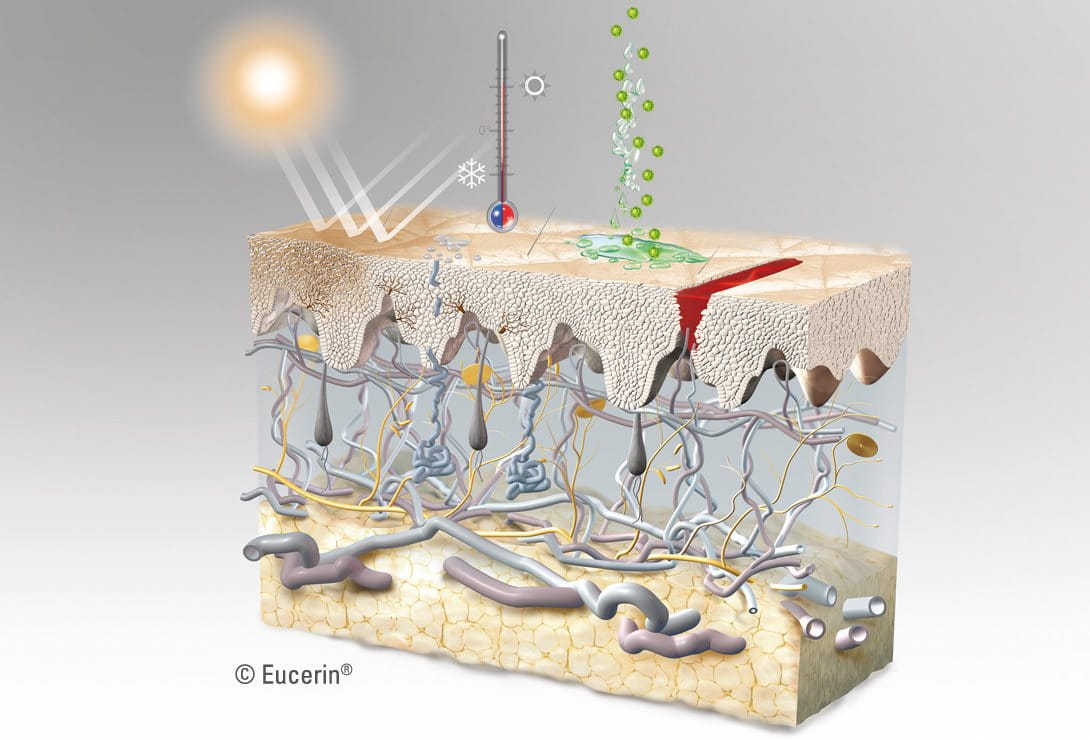

Cold, heat, water loss and radiation: As the outermost layer of the skin, the horny layer plays a pivotal role in protecting the body from the environment and limiting the amount of water lost from the epidermis.

It contains natural moisturising factors (NMFs) – derived from sebaceous oils of the horny layer including lactic acid and urea. These bind with water and help to maintain skin’s elasticity, firmness and suppleness. If these factors are depleted, skin loses moisture. When moisture of the horny layer falls to below 8 to 10%, it becomes rough, dry and prone to cracking.

When the skin is regularly exposed to UV rays, melanin production in the basal layer increases, skin thickens to protect itself and hyperpigmentation can occur. Read more in how sun affects skin.

The fat cells in the subcutis also insulate the body from cold and heat.

Pressure, blows and abrasion: Again, the epidermis forms the first layer of defence. The fat cells in the subcutis provide padding that acts as a shock absorber, protecting the muscle tissue and fascia (the fibrous tissue that surrounds muscles) beneath.

When skin is exposed to certain external stimuli the horny layer thickens, for example when calluses form on hands or feet that are exposed to repeated rubbing

Chemical substances: The buffer capacity of the hydrolipid film and the protective acid mantle helps to protect the body from harmful alkaline based chemicals. Read more in factors that influence skin.

Bacteria and viruses: The horny layer of the epidermis and its protective acid mantle form a barrier against bacteria and fungi. If something passes this first line of defence, skin’s immune system reacts.

Regeneration: Wounding impairs the functions of the skin, however, skin is able to repair and regenerate itself, ensuring it remains a versatile first line of defence.

Skin as a regulatory & sensory organ

The ultimate multi-tasker, skin plays many other roles essential to our health and well-being.

Temperature & fluid regulation: Skin perspires to cool the body and contracts the vascular system in the dermis to conserve heat. Sweat from glands in the epidermis also play a role in the body’s fluid balance.

Control of sensation: One of the key functions of the skin, the extensive network of nerve endings in skin make it sensitive to pressure, vibration, touch, pain and temperature.

Food source: The fat cells in the subcutis serve as important storage units for nutrients. When the body needs them, they pass into the surrounding blood vessels and are carried to where they are required.

Skin also plays an important psychological role. As the most visible indicator of health, the condition of our skin affects how we feel about ourselves and how others view us. When skin is healthy and problem-free it is able to do its job better and we feel more comfortable and confident.

Skin has various regeneration and repair mechanisms. The basal layer ensures a steady renewal of the epidermis, through continual cell division:

- If an injury is confined to the outermost skin layer, the damage (known as erosion) can heal without scarring.

- If the damage reaches the dermis and the basal membrane is affected (e.g. an ulcer) then scarring normally occurs.

Wound-healing follows several consecutive stages:

- Coagulating blood forms a membrane with a hard surface that sticks to the wound (a crust or scab).

- Dead and damaged cells and their connective tissues are broken down and dissolved by enzymes.

- Cells that protect the body by digesting harmful bacteria and dead cells become active. Lymphatic fluids flow into the wound.

- New cells – including capillary buds, connective tissues and collagen fibres – form in a process known as epithelisation.

This latter stage can be stimulated and supported by the application of topical products that assist healing (e.g. dexpanthenol).

Read more about the factors that influence skin health and about how to keep skin healthy in factors that influence skin, caring for skin on the body and a daily skincare routine for the face.

What happens when skin is damaged?

Healthy, problem-free skin is even in colour, smooth in texture, well hydrated and appropriately sensitive to touch, pressure and temperature. When skin’s structure is disturbed, its protective function and healthy appearance are compromised:

- It loses moisture and elasticity and can look and feel dry, rough, cracked and/or saggy.

- It becomes increasingly sensitive to external influences (such as sun and temperature changes) and is particularly prone to infection.

Infected skin can become inflamed as inflammatory immune cells move in to try and repair the damaged barrier and heal the infection. In the case of conditions such as Atopic Dermatitis and an itchy scalp, specialist treatment is often needed to break the vicious cycle of repeated itching and further infection and to help regenerate skin’s natural barrier.

Our brand values

We deliver a holistic dermo-cosmetic approach to protect your skin, keep it healthy and radiant.

For over 100 years, we have dedicated ourselves to researching and innovating in the field of skin science. We believe in creating active ingredients and soothing formulas with high tolerability that work to help you live your life better each day.

We work together with leading dermatologist and pharmacist partners around the world to create innovative and effective skincare products they can trust and recommend.